When I spoke to Auckland artist Sam Mitchell the day after she won the Wallace Arts Trust Paramount Award with her work Janus, a double portrait of an androgynous man with a blue face and a cat draped over his shoulder, she was still in a state of disbelief.

Mitchell, dressed in paint-speckled overalls, was trying to come to grips with the idea that in 2011 she will spend six months in her favourite city—New York. With the award comes a bronze sculpture by Terry Stringer and a six-month residency at the International Studio and Curatorial Programme in Brooklyn along with 26 other international artists. The residency represents a sense of ‘coming home’ for Mitchell who was born in Colorado Springs to American parents who emigrated to New Zealand in the 1970s, severing almost all their ties with their home country.

An almost manic collector and recycler of pop culture images—sourced from tattoos, comics, movies, magazines and the internet—and then re-sampled in fantastically irreverent and garishly bright paintings on perspex—Mitchell describes works like Janus as “portraits from the inside out”. As in traditional portraiture, viewers are given clues about the personality, state of mind and status of the subject, but the difference is these ‘clues’ are not misty landscapes, lap dogs or vases of flowers; instead they spread like unruly tattoos or subversive comic novels across the faces and bodies of Mitchell’s figures.

What gives portraits like Janus their incredible friction is the jarring disconnect between the figures themselves—often nostalgic, cute and inoffensive—and the dubious nature of the text and imagery superimposed on them. The Roman god Janus was often depicted as two faces or heads facing in opposite directions and so he was believed to look into the future and the past. Janus is also seen as the god of transition—of beginnings and endings—and as a representative of the middle ground between barbarity and civilisation.

Mitchell’s Janus is so androgynously pretty he could be a poster pin-up boy for gay and straight bedrooms alike, but the proliferation of text and images jiggling around inside the two figures tells a different story—one loaded with ambiguity, conflict and duplicity. It also refers to the repetition and circularity of certain events in history.

On the left figure are the words “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” and the paw of the cat (a colonial pet) obscures the fine detail of a Maori carving. The cat’s tail partly obscures a group of Aborginal figures and the words “Mr Robinson – Tasmania” appear caption-like beside the Aborigines. In Janus it’s obvious Mitchell is alluding to colonial misadventures and misdeeds—the painful history of indigenous peoples in New Zealand and Australia and the slippage between reality and myth surrounding this history. Mitchell explains that earlier this year she did a three-week stint in Newcastle at The Lock-up Cultural Centre Residency (which from 1861 to 1982 was the Newcastle Police Station). While there she watched the documentary series, First Australians, and learnt the tragic history of the Palawa tribe, the Tasmanian Aborigines. In the 1830s there was a lot of conflict between the Tasmanian Aborigines and the white settlers and in 1834 George Augustus Robinson (the Mr Robinson in the painting) persuaded the 135 surviving Palawa to surrender, giving them assurances they would be protected and provided for if they moved to Flinders Island off the north-east coast of Tasmania. The settlement was named Wybalenna, which means “black men’s houses”. Once there, they were forbidden to practice their old ways and many more of them died from influenza, poor food and despair.

As well as political and historical content, Mitchell plies personal truths and mythologies—in both her smaller more intimate watercolour works (some made on the covers and end pages of old books) and in her perspex paintings. Often there are references to events unfolding at the time she was making the work—the words “Bye Bye Kevin Rudd” sneak into the right Janus figure. And her approach to desire and sexuality is deliciously ambivalent, funny and playful as in the portrait of her father, based on a 1950s photograph of him wearing black-rimmed glasses and looking very conservative. In her version, titled Nineteen Eighty Five (the year her father died), his face is covered in tattoos of naked women. Other subjects Mitchell has painted include Michael Jackson, David Bowie (as Ziggy Stardust), notorious society women—the Mitford sisters—and Abraham Lincoln.

Clearly, her paintings create new myths—often mischievous and outrageous ones. “I’m a product of where I am, what I’ve listened to and read,” she says. “The work is my own churning up of all these facts and fictions and then spitting them out and almost creating myths out of myths again. In some respects I’m resubmitting a lie in a different way.”

In Janus and other portraits Mitchell reflects on Darwin’s concept of ‘natural selection’ which in turn gave rise to ‘memes’—objects, myths or forms of behaviour that, like genes, are passed on from person to person and are either adopted for their usefulness or abandoned to die a quick death. In the 1970s Richard Dawkins coined the term ‘meme’ in his book The Selfish Gene to refer to aspects of human culture and how they evolve in a way that is analogous to how genes evolve. A meme can be a song, a dance, a pair of earrings or an urban legend.

Commenting on the sexualised nature of her work Mitchell says, “I allude to a lot of things now; in earlier works I made it full-on and frontal but now you have to look for it. Yeah, they are very sexualised images … I do things that amuse me, and that is how I make my work. I’ve grown up in the gay community, my older brother is gay and I have gay guy friends. To me it’s a natural part of who I am in the community; it’s part of my culture and it’s part of who my friends and family are.”

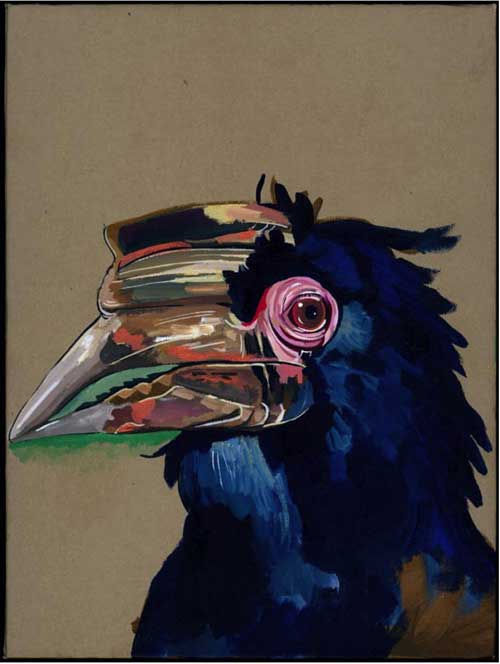

Mitchell shares an intense interest in history and portraiture with fellow artist and good friend Gavin Hurley whom she met when the two were studying at Elam. Recently they have begun to collaborate and exhibit their joint works. Hurley supplies Mitchell with a collage and she then paints graffiti over his image. Though their works are very different, there are startling similarities—a love of drawing and an acute awareness of the weight and quality of line, a fascination with exploring character and personality, and strangely, an affection for birds and animals. Hurley’s sea captains sometimes have exotic storybook parrots perched on their shoulders, and Mitchell’s series of portraits of domestic pets is ongoing—parrots, budgies, canaries and cats make regular appearances in her work, either as part of a larger work (like the two cats in Janus) or as stand-alone portraits without a hint of sarcasm—paintings your grandmother would adore.

Mitchell’s love for reverse painting (she says she has always steered away from canvas because she doesn’t like the feel of it, yet when I visited her studio she had three bird paintings on canvas propped on the mantelpiece) is interesting in light of the fact she has dyslexia. Reverse painting is a very old tradition in which the image is painted on the back of the glass (or in her case perspex), so when it’s turned around the image is reversed and seen through the glass. Mitchell loves the transparency and gloss achieved using this technique and it further accentuates her use of lavish, high-key colours. Like printmaking, which she studied at Elam, the outlines and highlights are done first and the background areas last.

“The overall blue layer is the sealant for all the chaotic, over-the-top, brightly coloured images on the inside,” she explains. “And if I made that layer flesh-toned, which I tried a few times, it alters the balance and intensity of the narrative inside. You look at the person first and then you are drawn into the little, tiny narratives inside, then you are drawn again to the person. But any colour other than the blues and the purples I use in the portraits tends to be too overwhelming and distracting. That blue really gives you a base to jump back into.”

The larger portraits on perspex have developed from her earlier watercolours on recycled books, and her combinations of text and imagery have steadily become more complex. She says, “When you source a found object you are limited by what you find—the book’s title and pages have a set parameter and so you have a limited amount of space to work within. I think it’s really good as a controlled experiment to work that way and I still enjoy finding book pages and covers. I never sit down with a preconceived idea of what I’m going to do. I sit down with a brush in hand and a whole pile of different kinds of references and imagery, which I flick through while I’m seated. There’s a constant obsession with getting that image as right as I can in my mind’s eye, even though people might have seen it before.”

“Being dyslexic hasn’t ever stopped me doing anything and the older I get, the more I realise that was the problem I had when I was growing up. When I looked at books I used to guess what the words were saying about the picture, and I think that gives you a very different way of looking at things because you start looking at the smallest things to pick up what the words are saying. I learnt to read quite late because I would always just tell the story, rather than reading the words. Now I read all the time, but my relationship to words has not always been easy.”